American gymnast Simone Biles withdrew from several Olympic events earlier this summer, after experiencing a case of “the twisties” — what gymnasts describe as losing control of their body mid-trick and losing sense of where they are in the air. The sensation is not only disorienting, it’s dangerous and can lead to serious injury.

Following Biles’ decision to forego the team final, various former gymnasts posted to Twitter about their own experiences with the twisties that resulted in broken bones, concussions and dislocated vertebrae. U.S. Olympian Dominique Moceanu, who medaled in gymnastics at age 14, tweeted, “In our sport, we essentially dive into a pool w/ no water. When you lose your ability to find the ground — which appears to be part of @Simone_Biles decision — the consequences can be catastrophic.” (Her video is compelling.)

The condition is similar to the so-called “yips” in other sports, representing a moment where, suddenly, an athlete’s brain and body lose connection and muscle memory fails. Through their countless hours of training, athletes literally wire and rewire their brains to perform complex movements with a high degree of reliability and precision. So what’s happening when a case of the twisties strikes? I researched to find out.

Your Brain and the Twisties…What Is Happening?

The yips and twisties crop up when athletes suddenly fail to perform the motor skills they’ve drilled into their brains in practice. But how do they pick up those skills in the first place? Part of the motor-learning process involves learning what physical sensations to expect when executing a new skill. It is thought that balance during complex motions, such as gymnastics, requires a real-time comparison between the brain’s expectation of sensory input (the “internal model”) and the actual input.

While in motion, the brain takes in sensory information from the eyes; proprioceptive nerve cells, which relay information about body position to the brain; and the vestibular system, the sensory system in the inner ear that controls the sense of balance. The brain then integrates all these signals and compares them to the internal model of what the motion should feel like, based on past experiences.

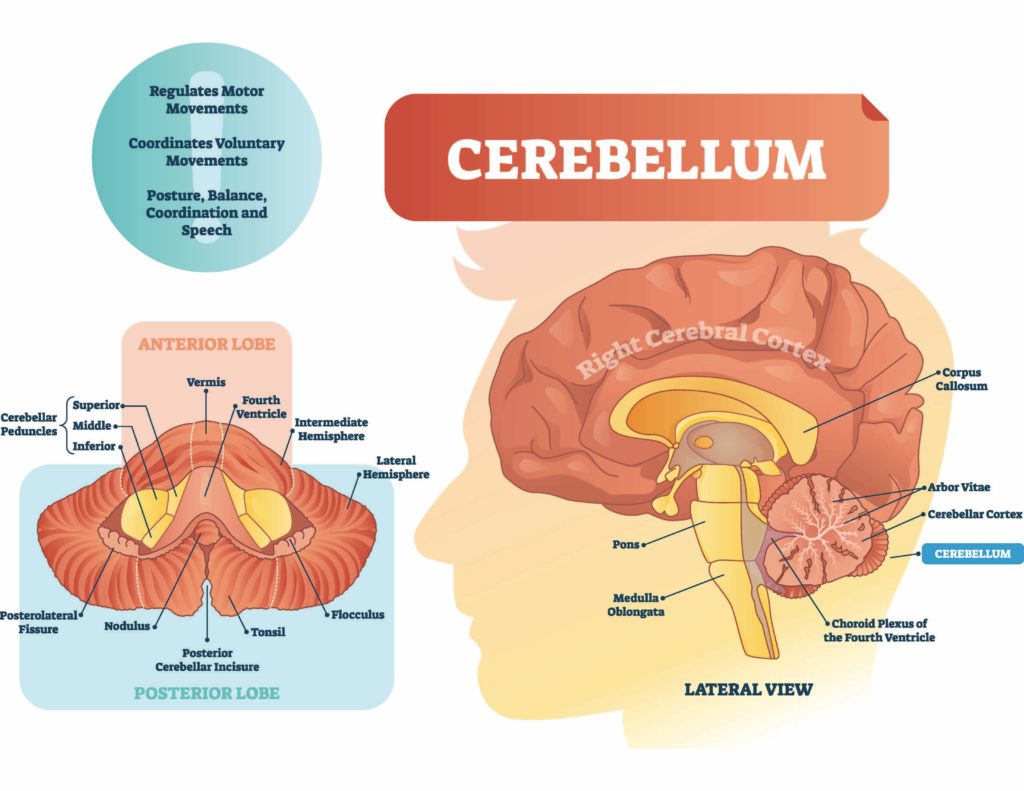

The cerebellum, located at the bottom and back of the brain, plays an important role in generating these internal models of movement; the cerebellum also watches out for any mismatches that occur between the expected sensations of a motion and the actual ones that happen in real-time. I

f it senses any unexpected motion — say a gymnast’s back arcs a bit more than usual during a release from the uneven bars — the cerebellum quickly shoots a message to the spinal cord, which then switches on reflex pathways that help the body adjust itself. (You also see this in diving where the diver may have under or over rotated and they’ll make corrections that may cause them to enter the water incorrectly, i.e., big splash!)

Research has shown that the cerebellum actually computes unexpected motion within milliseconds so that it can send an appropriate signal to the spinal cord to rapidly adjust our balance. In addition to switching on certain reflexes when needed, the cerebellum also suppresses reflexes that might otherwise prevent athletes from executing certain skills (Scientific American). For instance, with training, ice skaters can learn to execute super-fast spins with their heads thrown back; the cerebellum quells reflexes that would pull the body back into an upright position, as well as those that control eye motion and could make the skater dizzy.

Can Athletes Train to Prevent the Twisties?

Through practice, athletes build and refine very complex internal models of their movements, meaning they can develop a keen sense of when and how to adjust their bodies to nail a motion each time, whether they’re flipping onto a balance beam, executing a flip turn in the pool or diving off a platform. In the early stages of learning a skill, they rely on explicit instructions, visual cues and trial-and-error to learn what to do to execute a given skill.

“When you are first learning a motor skill, error is actually a great teacher,” per Gregory Youdan, a human movement scientist and a committee member of the International Association for Dance Medicine and Science. Errors generate feedback from the body’s sensory systems, and in the case of athletes, also prompt feedback from their coaches; this process of making errors, receiving feedback and making corrections helps the brain adopt new motor patterns efficiently.

In later stages of learning, athletes can start to focus more on proprioceptive cues and tune into how their bodies feel moving through the skill. With repetitive practice, the skill becomes so well-learned that it is nearly automatic and can be performed with very little conscious control over the movements. Therefore, with training, athletes no longer need to think their way through the mechanics of every flip, throw or leap. It becomes a programmed skill.

When Can the Twisties Hit?

That said, when under pressure, athletes may try to take more conscious control of their motions, and this process can actually lead to errors, and, you guessed it, the dreaded twisties. An athlete may try to compensate for increased physiological or cognitive stress or a lack of confidence by trying to consciously control movements that were previously automatic. The resulting motion tends to be less fluid, less accurate, more strenuous and more error-prone than it otherwise would be.

Some degree of stress can be helpful, as it can boost alertness and focus one’s attention, but too much stress can interfere with the brain’s ability to initiate learned motor sequences (Frontiers of Psychology). This may be related to the stress-induced release of glucocorticoid hormones, such as cortisol, since the motor cortex, cerebellum and spinal cord all carry receptors for these hormones. Without that learned motor pattern being initiated automatically, a gymnast can experience the twisties.

Sports psychologists help athletes develop strategies to offset the potentially detrimental effects of stress on their performance. These strategies include practicing relaxation techniques like diaphragmatic/meditative breathing and using mental imagery to re-enact the experience of executing a skill under pressure. Athletes can also develop a routine of rehearsed thoughts and behaviors to help get them into a performance-ready mindset. Coaches and athletes can also try replicating some of the stressful aspects of competition during practices, so that the stakes feel more “real” when it comes time to compete.

When the Twisties Strike, What Do You Do?

Some gymnasts find they have to retrain the skill that tripped them up, sometimes starting with the basic components and working their way back up to the fully-realized trick, The Los Angeles Times reported. Sports psychologists also work with athletes to determine whether a particular skill itself triggered the twisties, or if specific environmental factors were more to blame.

JaNay Honest, former University of California, Los Angeles gymnast, said in the LA Times article that she used mental imagery to overcome a bad case of the twisties. She envisioned herself nailing skills over and over; she then moved on to physical training with foam pits and extra mats. Prior to this retraining, though, she and her coaches began crafting her routines to avoid twisting altogether, as that skill kept provoking on the terrifying sensation. (This is what Simone Biles did when she returned to competition on the balance beam.)

“It’s kind of like forgetting how to twist your body in the air,” she told the LA Times. “It’s really scary because when you’re doing a skill like Simone does … it’s really dangerous.”

Eduardo Elizondo

MDBoard-Certified Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation

Board-Certified Electrodiagnostic Medicine

Certified Life Care Planner

Interested in reading more articles about athletes? Check these out!