In part one of this series on rotator cuff injury and partial tears, we explained the non-surgical approach that facilitates the body’s innate capacity to heal and repair – regenerative medicine. This technique can be utilized to restore the integrity of any joint in the body, but is used frequently in the shoulder joint. Why is the shoulder so susceptible to dysfunction and injury?

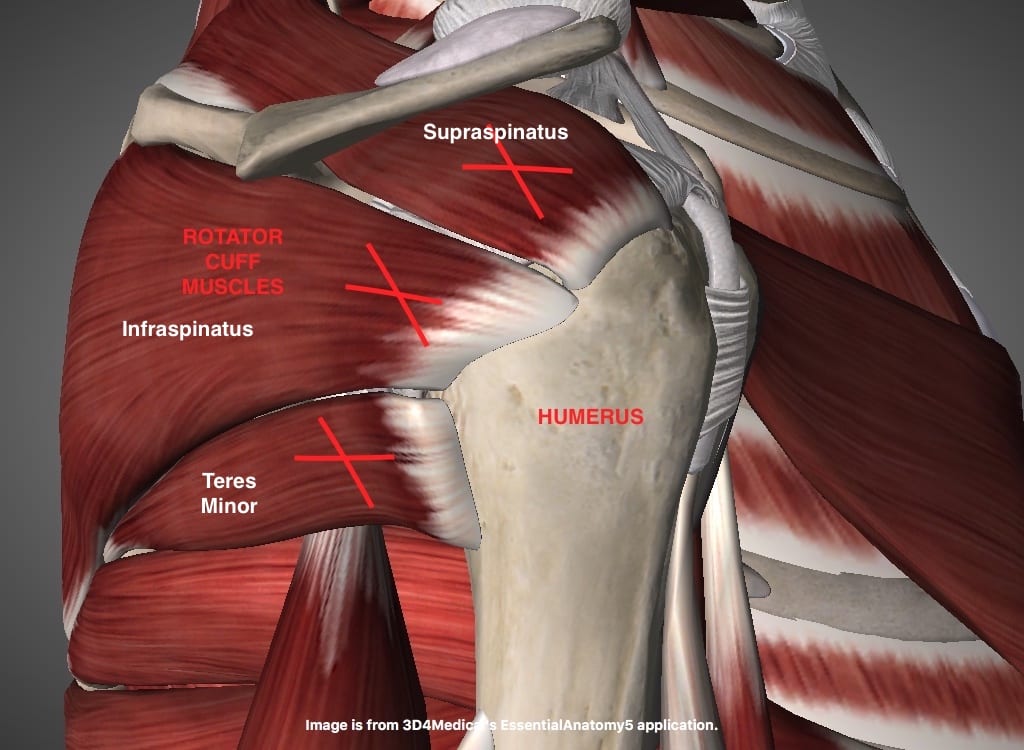

The short answer is freedom. Our shoulders have, by far, the greatest freedom of motion of any joint in our body. With this freedom, comes the challenge of stability. The rotator cuff is a group of four muscles that hold the head of the humerus (arm bone) securely into the socket of the shoulder, much like the muscles of the eyeball hold it into its socket. (Figure 1) These structures require the delicate balance of stability while still allowing the freedom required for full, functional reach and range of motion.

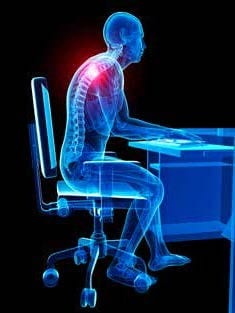

This stability comes from three sources: the joint capsule, the rotator cuff tendons, and the symphony of neuromuscular control of all the muscles that attach to the arm, shoulder blade, spine and ribs. It is because of these numerous attachment points that posture becomes such an important aspect of shoulder biomechanics and function. When we look at Figure 2 above, we can see that when our shoulders round forward the muscles of the rotator cuff are pulled on stretch. They are lengthened and doing their very best to hold on to the head of the arm bone and keep it in that socket. This is a place that not only increases the wear and tear on the rotator cuff tendons, but also sets the shoulder up for injury.

So we are told to, “Sit up straight!” Unfortunately this simply exchanges one poor movement pattern for another. When we pursue that chest out and shoulders back posture we tend to squeeze our shoulder blades together and raise our rib cage. This too produces increased tension and poor neuromuscular balance because the stabilizers that help us maintain width and neutral position of the shoulder blades are inhibited by the pull of other muscles. Also, and no less important, the elevated ribcage now decreases the stability of our core. In short, the shoulder girdle and arms no longer work from a stable base of support because our core stability is now compromised. Coordination between the core and the shoulder girdle is required to decrease rotator cuff strain and injury.

Figure 3 gives us a better example of a released neutral posture. The ribcage is down, the shoulders are wide and neutral, and the rotator cuff gently holds the head of the arm bone in the socket without a tug-of-war between the muscles. I often share my favorite quote with my patients, “Nothing must be added where nothing else is needed.” So it is in life – it is with our shoulders – the right muscle, at the right time, in the right amount makes for a happy rotator cuff.